Guest Post by Sofie Koonce, PAS Intern

Studying history often becomes an exercise in puzzle solving.

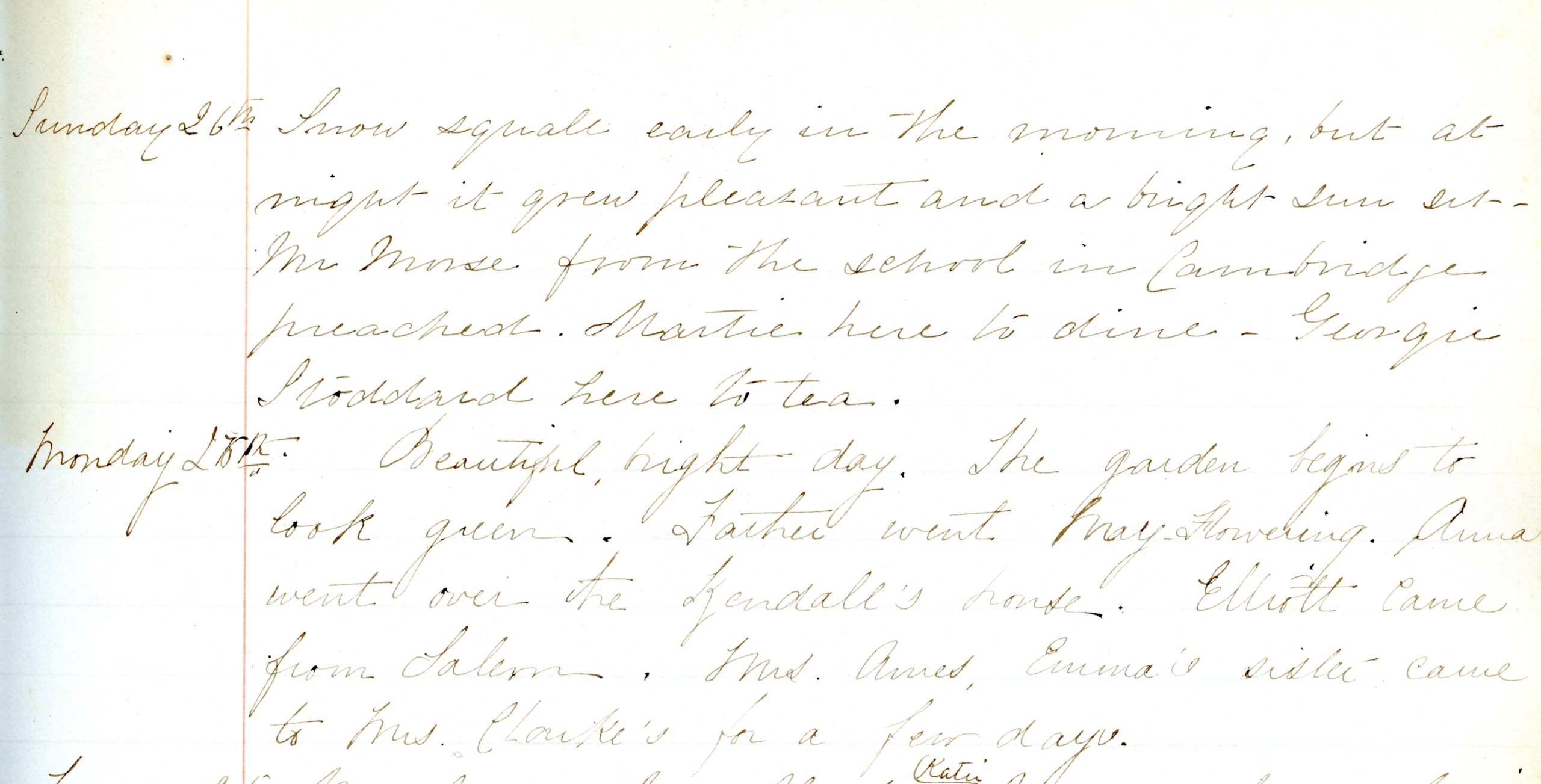

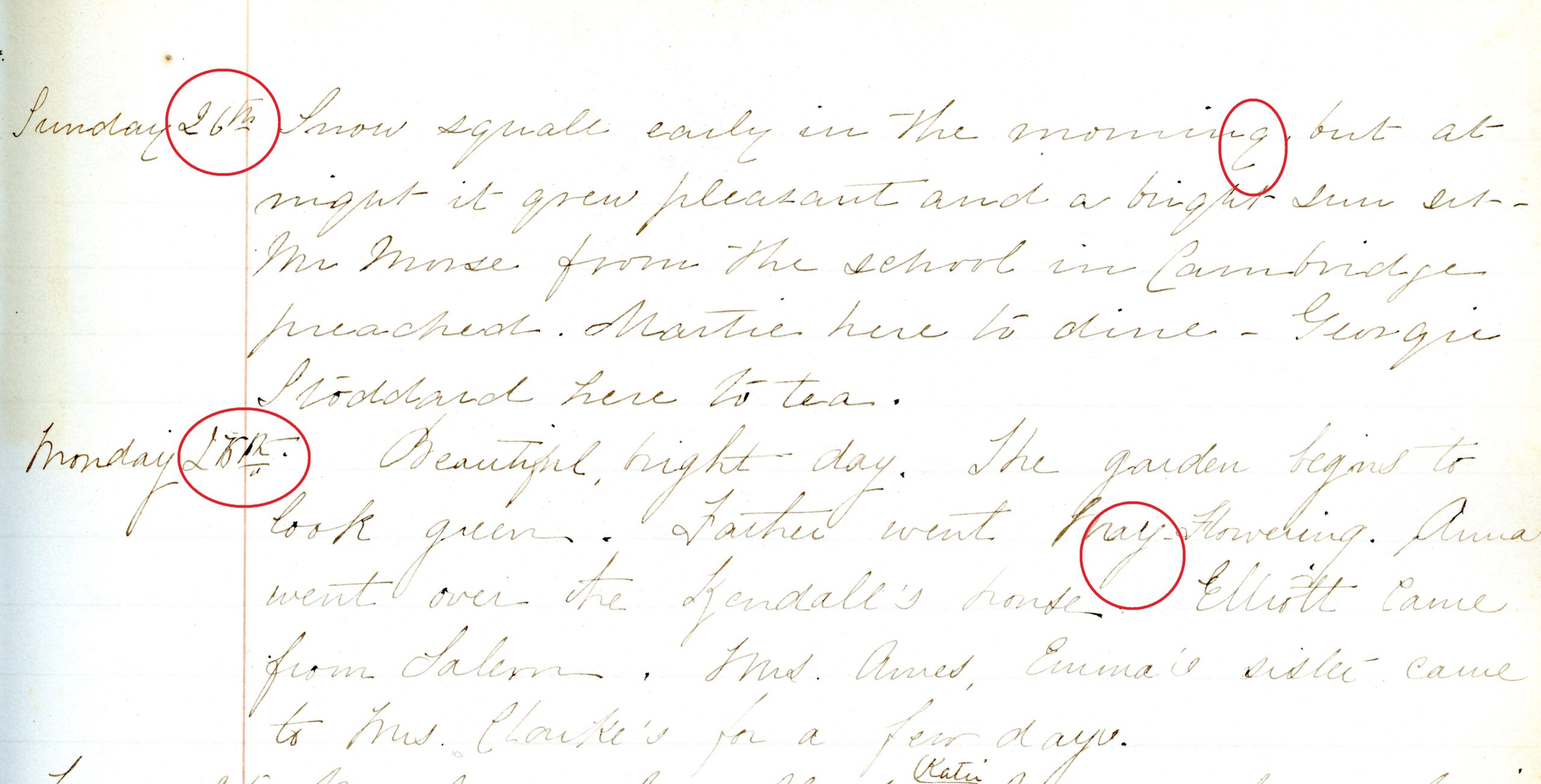

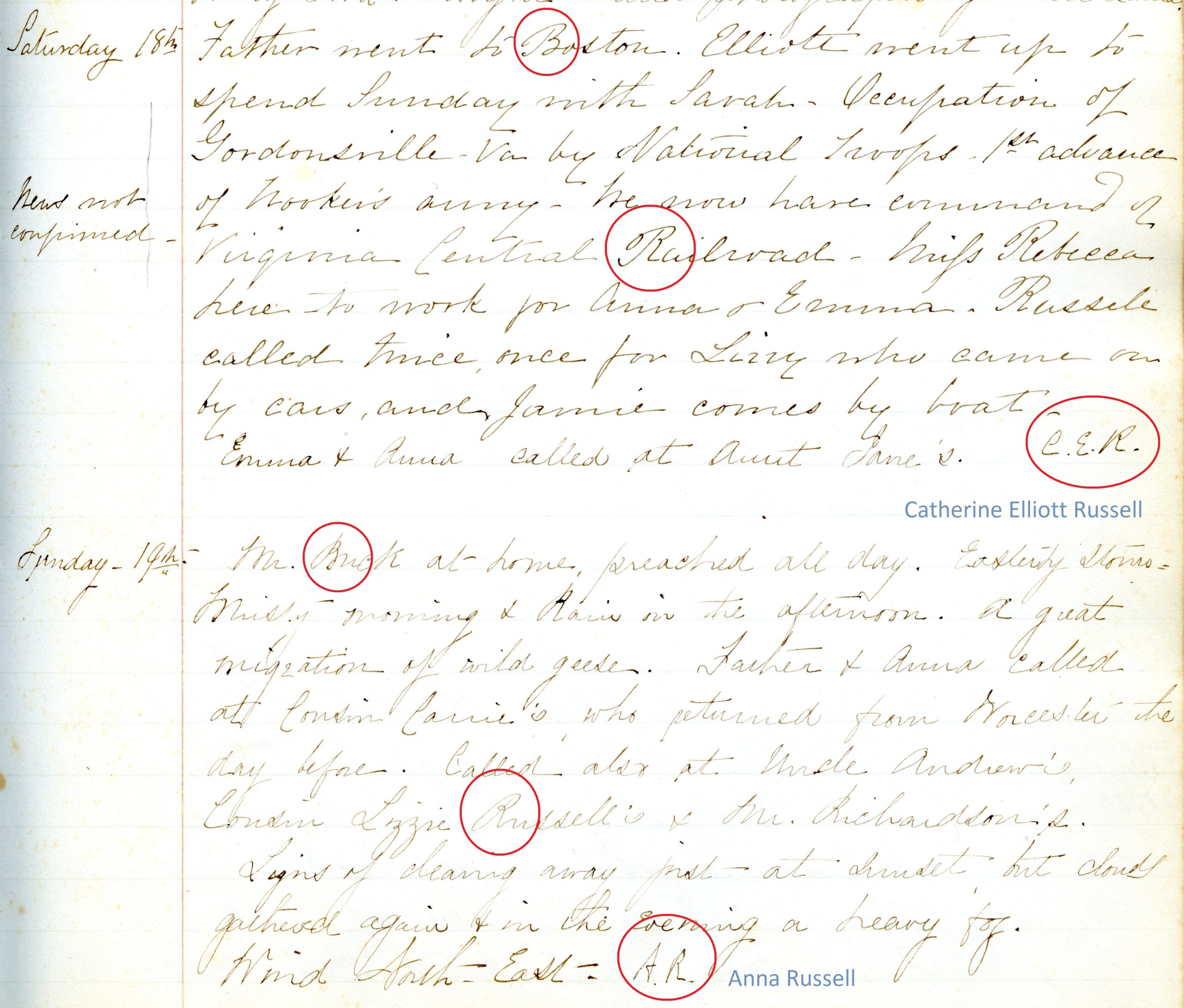

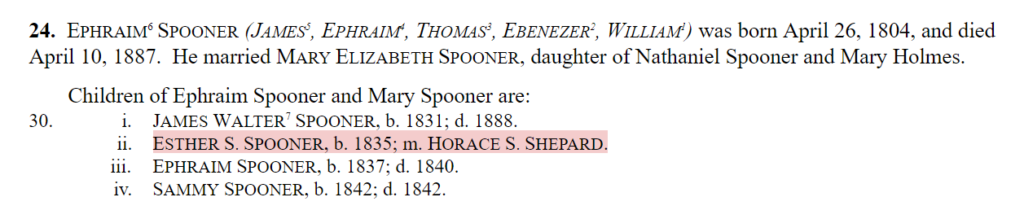

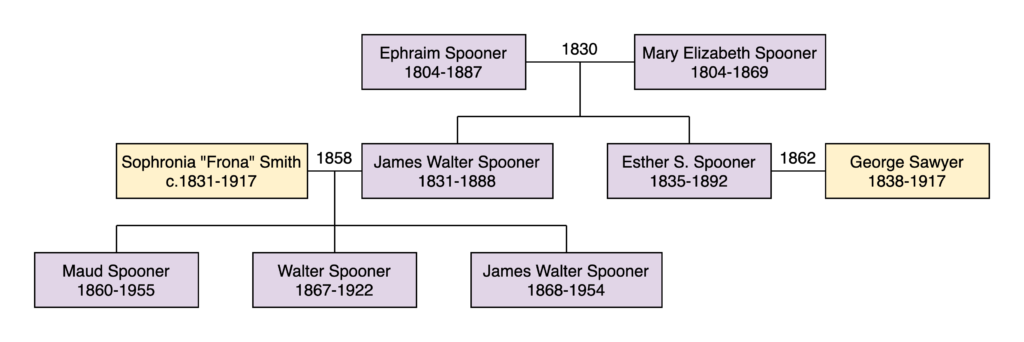

One of my internship tasks has been transcribing letters to and from members of the Spooner family. The majority of the ones that I looked at were written by Esther S. Spooner (1835-1892) to her parents, Ephraim and Mary Elizabeth Spooner. The letters mention her brother, James Walter Spooner, and his wife, Sophronia “Frona” Smith, as well as their daughter, Maud, and sons, Walter and James.

Beyond the immediate family, I found myself faced with a cast of unfamiliar characters from the extended Spooner family. It was important that I learned who these people were so that I could better understand the dynamics between them. In order to do that, I turned to genealogy.

The Antiquarian Society has a genealogy of the Spooner family that helped me immensely in untangling the web of names mentioned in various letters. However, repetition of names within the family was not uncommon, so I had to rely on context clues to figure out which person by that name was being referred to. These clues were often things like titles—Aunt, Uncle, Cousin—or indications of a person’s age. Sometimes combinations of names were helpful as well. For example, if Esther Spooner referred to a Hannah and Charles together, it was generally safe to assume that she meant her Aunt Hannah (Bartlett) Spooner, whose son was named Charles W. Spooner.

As I went through the letters, I found a couple written in 1871 that confused me. In them, Esther Spooner referred to a man named George. From the context provided in the letters, I inferred that George was her husband, but the genealogy I had told me that Esther Spooner married a Horace S. Shepard.

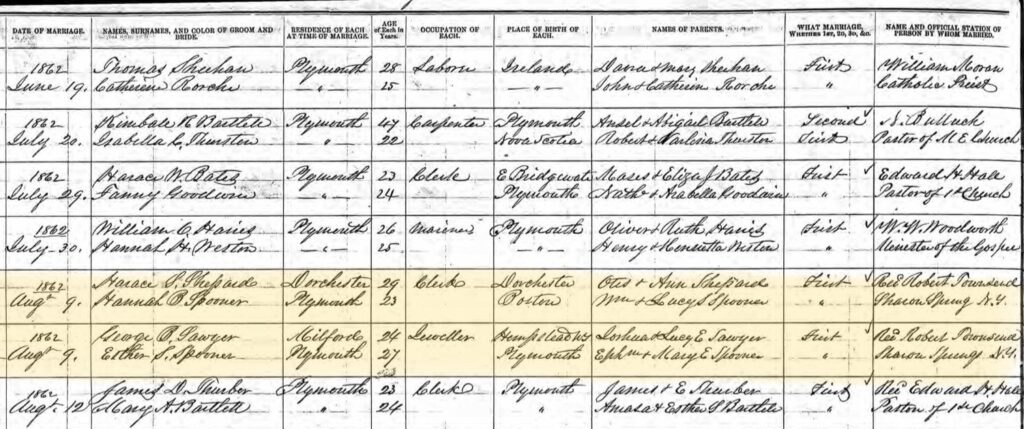

I turned to Ancestry to see if I could confirm Esther’s marriage to either Horace Shepard or the unknown George. A record of marriage revealed that Esther Spooner married a George Sawyer in 1862. So who was Horace Shepard? Right there, on the same document, I found that Horace married a Hannah B. Spooner. The two couples were married on the same date (August 9, 1862) in the same place (Sharon Springs, NY).

I now understood how Esther’s husband could have easily been incorrectly identified as Horace B. Shepard by a genealogist who mixed up the two Spooner brides. I concluded that Esther and Hannah must be cousins. However, in the Spooner family genealogy I could not find a Hannah B. Spooner who would have been 23 in 1862. Although her parents are named on the marriage record, I could not match them to anyone listed in the genealogy either. Back to Ancestry!

Eventually PAS Executive Director Anne Mason successfully identified Hannah as the granddaughter of Bourne and Hannah (Bartlett) Spooner of Plymouth. Bourne, the founder of the Plymouth Cordage Company, was the brother of Esther’s mother, Mary. Hannah was the eldest child of Bourne’s son, William, and his first wife, Lucy (Gibbs) Spooner. Lucy died when Hannah was only a toddler and she was raised by her grandparents. Eventually her father moved to Michigan and remarried, but Hannah remained in Plymouth. She and Esther were first cousins once removed. Although members of a different generation of their family, they were only four years apart in age. The story of their double wedding is a fascinating one that we are saving for a future post!

While the family genealogy was a helpful resource, nothing beats primary sources—though even those can be misleading sometimes!

I’m a very visual person, so I found that transferring the information from the genealogy into a family tree helped me to understand the connections. Laying everything out in one place made it much easier to see how relationships worked within the family. Below is just one part of the sprawling Spooner family tree, with the names and dates that I’ve been able to correct or add so far.

Genealogical research is one way I’ve been getting to know the Spooner family. Reading their words to each other and learning the natures of their relationships has brought them to life. One of my favorite parts of studying history is the reminders that people from the past were just as human as we are today, and those reminders are a key part of the puzzle that we solve to gain a more complete understanding of history.

Sofie Koonce is a junior at Smith College in Northampton, MA, where she is a Classics major with a concentration in Book Studies. The Book Studies concentration program encourages students to delve into the world of the written and printed word and explore careers that involve working with manuscripts and printed materials. Sofie is back in her hometown of Plymouth interning with the Antiquarian Society remotely during the winter term. Post graduation, she plans to pursue a graduate degree in Library and Data Science.