Guest Post by Sofie Koonce, PAS Intern

One of my internship projects is transcribing the Russell family journal. This manuscript was for many years misidentified as the journal of just one person: Catherine Elliott Russell (1840-1916). A closer look reveals that it was kept by multiple members of the Russell family, who would take turns making entries. The Russells lived at 32 Court Street in the beautiful “Russell Manor” and were a wealthy, well educated, and very social family. The Russells began this journal in February of 1863 and continued it through February of 1864. There are also a few entries at the end from 1904, when the journal was rediscovered by one of the surviving family members.

Transcribing a family journal can be a little more complicated than transcribing a letter, especially when the journal’s several authors don’t make a habit of signing off their entries. It becomes even more confusing when authors refer to themselves by name instead of in the first person, which means I can’t assume they didn’t write the entry if they’re mentioned in it. As a part of the transcription process, I’ve been attempting to figure out which family members wrote what. A lot of this comes down to handwriting analysis. There are essentially two steps: 1. parsing out different handwritings and 2. matching those handwritings to people.

Some family members have distinct handwriting, which makes it much easier to identify their entries. Other family members have handwriting that appears the same at a glance (and sometimes at more than a glance…) which is significantly trickier. In those cases, I have to look at little quirks that characterize each person’s handwriting.

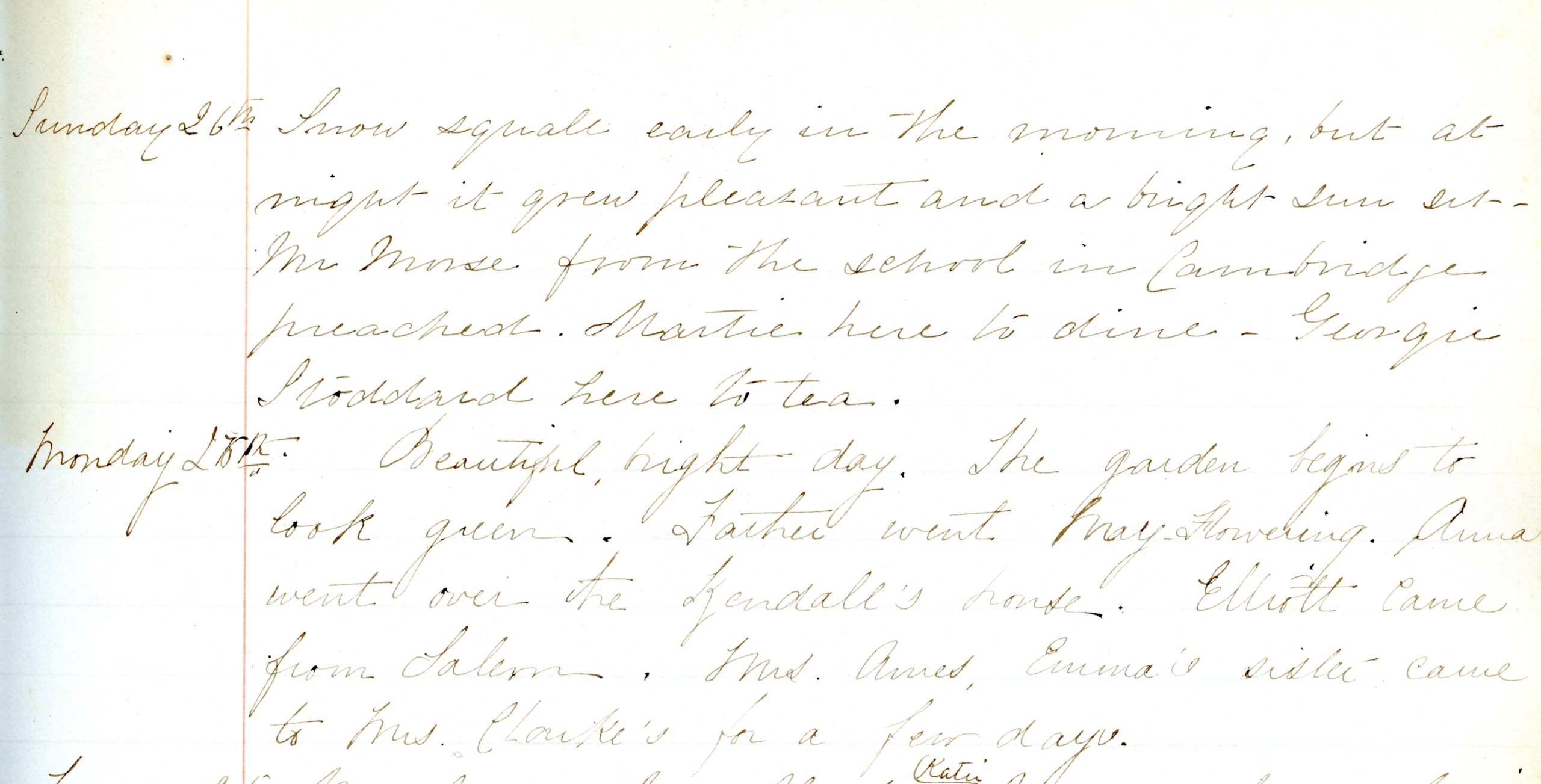

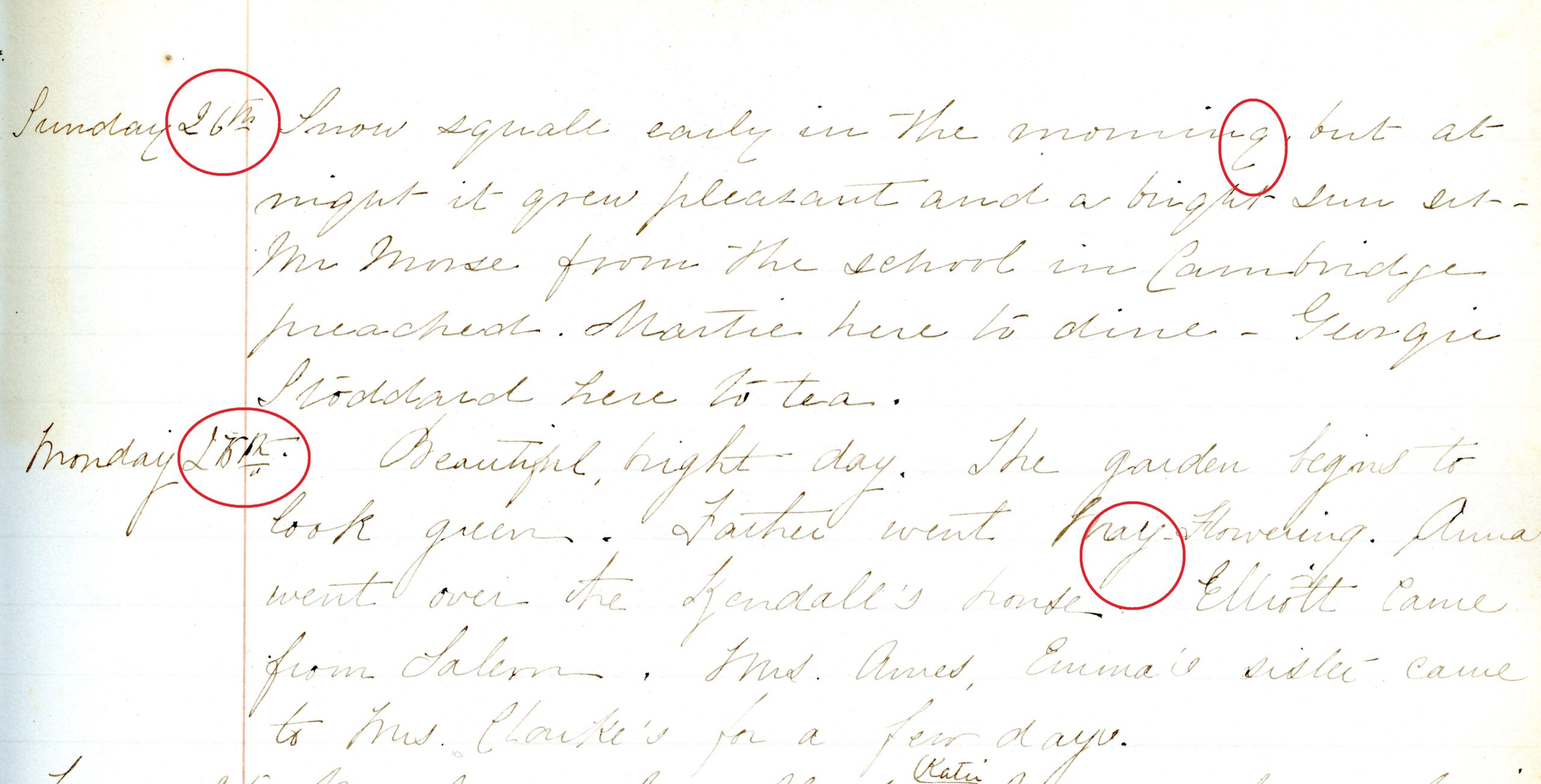

In the picture above, the entries for Sunday, April 26 and Monday, April 27, 1863 were written by two different people, Catherine Elliott Russell and her sister, Anna Russell (1835-1900). When placed directly next to each other like this, it’s easier to see that they’re different, but they are similar enough to be confusing. I had to look closely.

One of the things that really helped me was how the sisters wrote the dates. Catherine typically underlined the “th” after the date once or twice. Anna would underline the “th” and then draw two dots underneath it, as seen here. The difference is slight, but consistent. Also, Catherine draws the tails of lowercase letters (y, g, j) curving to the right, while Anna more traditionally loops them.

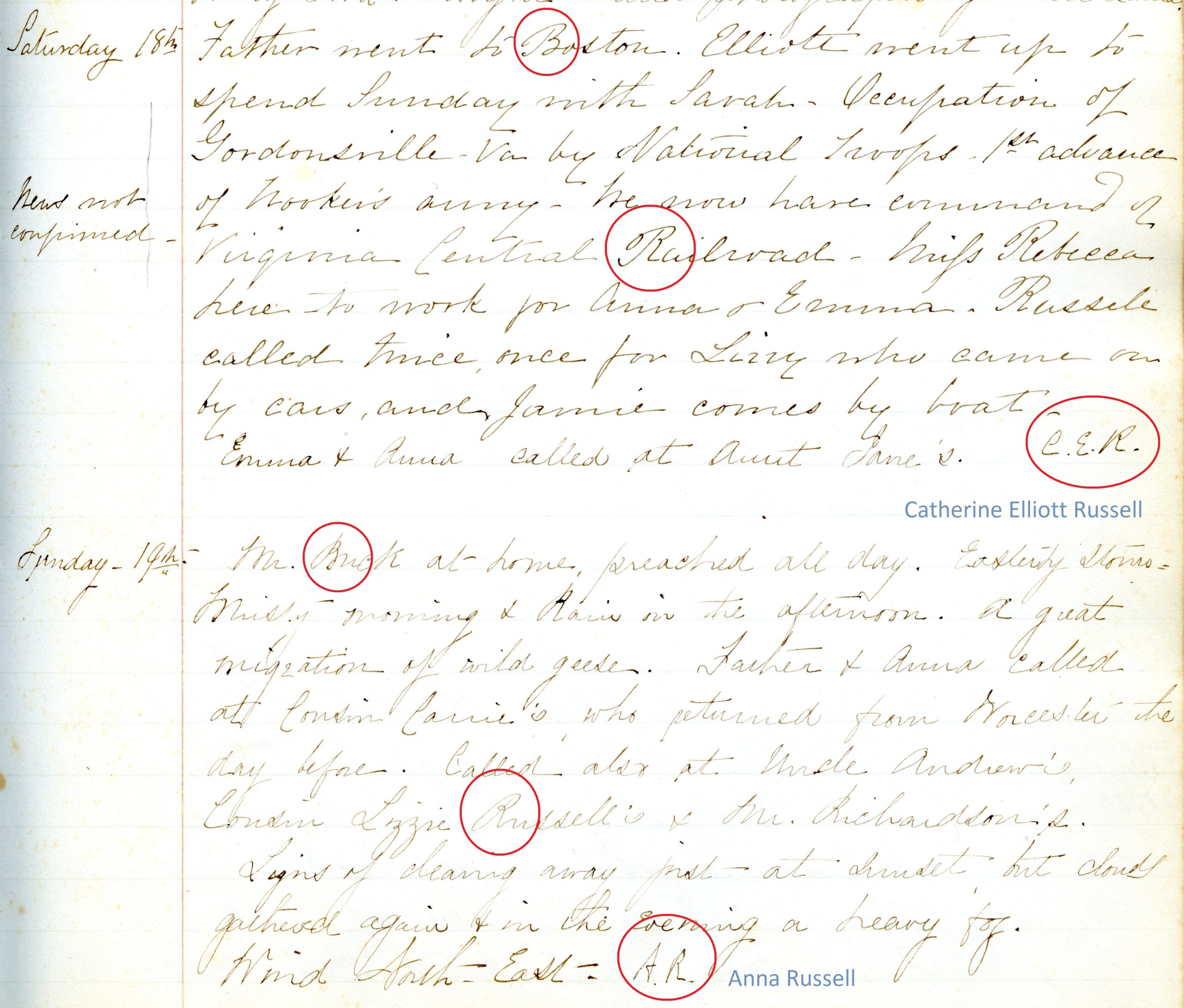

There are a few entries initialed by Catherine and Anna that can serve as a guide for decoding their handwriting. On the entries from Saturday, April 18th and Sunday, April 19th (pictured below) I noticed that the sisters have distinct ways of writing capital Rs and Bs. Catherine writes a downstroke, then lifts her pen to make the rest of the letter. Anna loops the downstroke into the rest of the letter, creating a noticeably different result.

These small differences were particularly helpful when the handwriting samples weren’t adjacent. Most often, I was using Catherine’s distinctive tails to pick out her handwriting. It is not surprising that the sisters might have similar handwriting, but being able to pick up on their unique quirks is key to telling them apart!

How did the journal become part of the Plymouth Antiquarian Society’s archival collection? In 1871 Catherine married William Hedge (1840-1919), the youngest son of Thomas and Lydia Hedge, owners of what is now the Hedge House Museum. Catherine inherited the Russell family home at 32 Court Street after her father’s death in 1875. It was here that she and William raised their three children (daughter Lucia and twins William and Henry). Possibly the journal remained in the house until it was given to the Society by Russell/Hedge family descendants. The Society’s collections include many objects and manuscripts collected by Catherine, who was interested in saving records of Plymouth’s past, especially those produced or used by women: needlework samplers, clothing, and recipes.

Sofie Koonce is a junior at Smith College in Northampton, MA, where she is a Classics major with a concentration in Book Studies. The Book Studies concentration program encourages students to delve into the world of the written and printed word and explore careers that involve working with manuscripts and printed materials. Sofie is back in her hometown of Plymouth interning with the Antiquarian Society remotely during the winter term. Post graduation, she plans to pursue a graduate degree in Library and Data Science.