Part 1 of a special series to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment

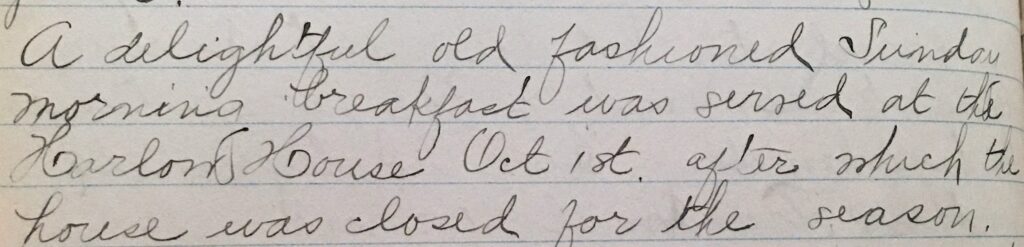

The campaign for women’s suffrage began in earnest after the Women’s Rights Convention held in Seneca Falls, NY in 1848. Plymouth abolitionist Zilpha Harlow (1818-1891) attended the first national Woman’s Rights Convention in Worcester, MA in 1850. Also in attendance was Nathaniel Bourne Spooner of Plymouth. The couple married in 1851 and worked diligently for the anti-slavery cause over the next decade.

After the Civil War, the Spooners shifted their focus to the expansion of women’s rights, often hosting lectures and other gatherings in Plymouth. In November 1870 Margaret W. Campbell (1827-1908) led a two-week speaking tour of Plymouth County for the American Woman Suffrage Association. Born in Maine, Campbell was one of the most popular public speakers on suffrage and campaigned across the nation. She reported in The Woman’s Journal, “We had a very good meeting in Plymouth, although not a large one, for the conservative element is strong there.”

On November 24, 1873 Plymouth’s Woman Suffrage Political Club was formed. Julia Ward Howe and Lucy Stone, co-founders of the American Woman Suffrage Association, attended the assembly held in Davis Hall on Main Street with an audience of about 500. The Club began meeting regularly in the home of Zilpha H. and Nathaniel B. Spooner on North Street.

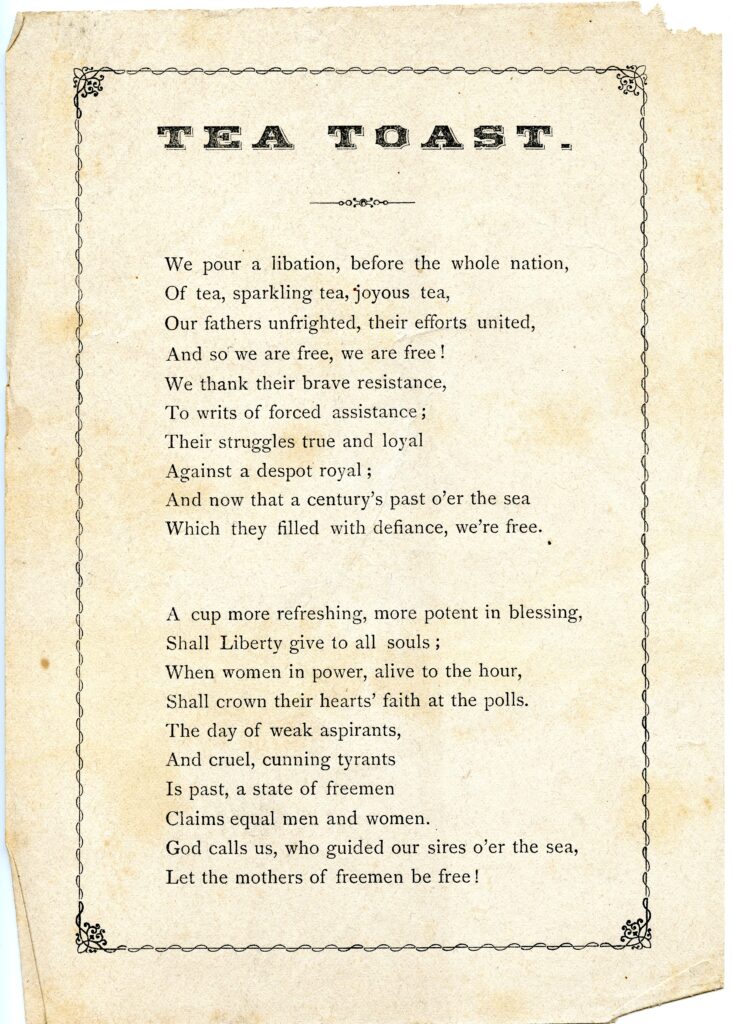

An unsigned toast in the Plymouth Antiquarian Society’s archival collection envisions an extension of the liberty won in the American Revolution “When women in power, alive to the hour,/Shall crown their hearts’ faith at the polls.” The toast is undated, but was probably printed around 1873. (The author proclaims “a century’s past o’er the sea/Which they filled with defiance”, an allusion to the Boston Tea Party of December 16, 1773.) It is likely that the toast was used at an early gathering of the Woman Suffrage Political Club in Plymouth.

Tea Toast

We pour a libation, before the whole nation,

Of tea, sparkling tea, joyous tea,

Our fathers unfrighted, their efforts united,

And so we are free, we are free!

We thank their brave resistance,

To writs of forced assistance;

Their struggles true and loyal

Against a despot royal;

And now that a century’s past o’er the sea

Which they filed with defiance, we’re free.

A cup more refreshing, more potent in blessing,

Shall Liberty give to all souls;

When women in power, alive to the hour,

Shall crown their hearts’ faith at the polls.

The day of weak aspirants,

And cruel, cunning tyrants

Is past, a state of freeman

Claims equal men and women.

God calls us, who guided our sires o’er the sea,

Let the mothers of freeman be free!

(PAS Archival Collection 2009.5.11)