Part 5 in a special series on the Pilgrim Breakfast

Since the 1930s guests have been charmed by the costumed volunteers serving food, singing, and demonstrating crafts at the Pilgrim Breakfast. We continue to wear 17th-century style costumes – even though they can be quite uncomfortable on a hot summer day!

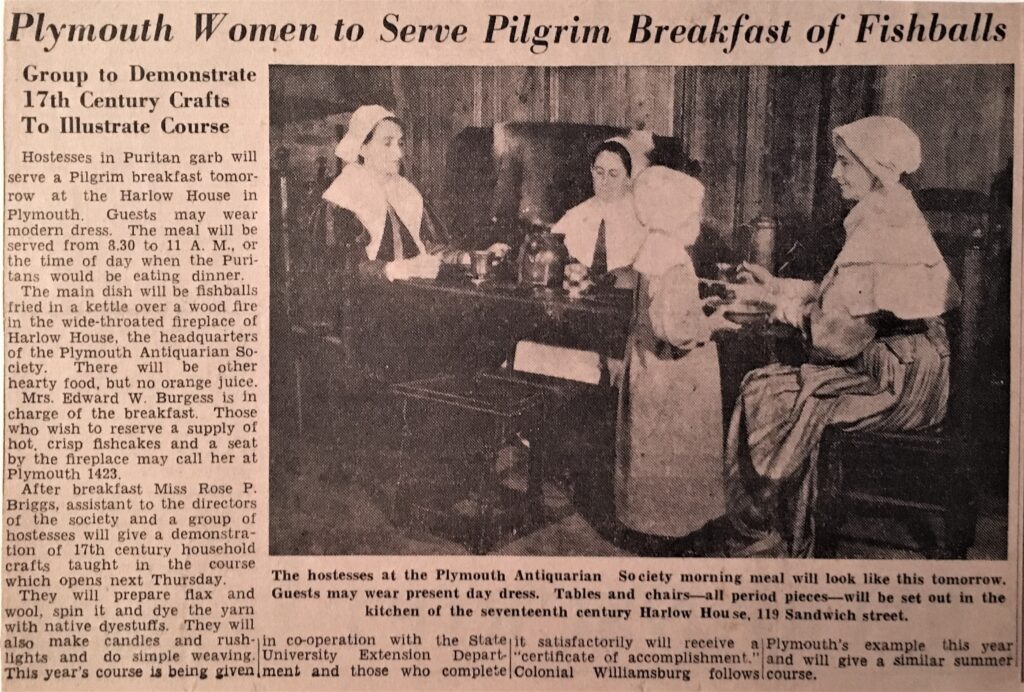

The first Antiquarians diligently researched and recreated period clothing, seeking to understand its impact on everyday activities. They made costumes to wear at the Harlow Old Fort House, undoubtedly following the lead of Rose T. Briggs, who designed the costumes for the first Pilgrim Progress held in the summer of 1921 for Plymouth’s tercentenary (a tradition that also continues today). The 19th-century image of Pilgrims in all-black ensembles with large buckles on their hats gradually gave way to more historically accurate representations.

The costumes we use today have been passed down by many generations of Antiquarians – which means we have an assortment of styles to choose from. Most pieces were made for the Pilgrim Breakfast by our members, although there are a few ready-made items. Instead of the wool and linen used by 17th-century colonists, our costumes are mostly made of cotton. We also use modern conveniences like zippers.

Our goal is to add a festive element to our event, not to perfectly recreate 17th-century styles. Girls and women wear a skirt and bodice, apron, coif (cap), and kerchief. Boys and men wear breeches and a shirt. We always recommend leather shoes if our volunteers have them, but our priority is that everyone be equipped with comfortable and safe footwear for a busy morning running across the yard.

The costumes aren’t marked with modern sizes, which makes dressing a crew of over 20+ volunteers a unique challenge. The annual fitting before the big day provides a special opportunity to note the passage of time as our youngest volunteers outgrow the previous year’s costume. They return year after year, ascending the ranks from tussie mussie sellers to muffin distributors to assistant servers and (finally!) senior servers, fully responsible for serving the guests at one or two tables. We think the Pilgrim Breakfast’s future is ensured; we’re grateful for the many young history lovers who view it as an essential part of their summers.

Interested in creating your own Pilgrim costume for Plymouth’s 400th anniversary? Learn more from local reenactors and material culture experts: New Plimmoth Gard, Society of Mayflower Descendants and Plimoth Plantation.

A Gallery of Antiquarian Costumes through the Years

- Elizabeth St. John Bruce with unidentified man at the Harlow House, ca. 1930 (PAS Archives)

- Edith Stinson Jones with unidentified man, ca. 1955 (PAS Archives)

- For many years Joann Doll demonstrated spinning at the Harlow House. Here she uses the walking wheel in 1990.

- PAS Executive Director Anne Mason and her mother, Elizabeth Reilly, after singing 17th-century tunes at the Spooner House for the annual Pirates Ashore event in 2015. Elizabeth is wearing Joann Doll’s costume.

- Steve Mattern, captain of the New Plimmoth Gard, at the Pilgrim Breakfast in 2019. The gardsmen always wear historically appropriate styles.

- PAS President Ginny Davis in the Harlow House in 2014.